Again, I wish to state unequivocally that the comments presented here are my own and not that of any organization of which I may be a member, nor of any past employer.

Summary

The National Park Service has released for comment a revision of Bulletin 38, Identifying, Evaluating, and Documenting Traditional Cultural Places. While the draft greatly expands the guidance offered to nominating historic places that are important to traditional communities, it is hampered by limits imposed by existing legislation and regulation. Regardless of how encouraging the guidance is in trying to bring more traditional cultural places (TCPs) into the National Register, nominated places must still fulfill all current existing standards for significance and integrity. In offering this guidance, the authors have also exposed a problem with the entire construct of a traditional cultural place. In describing what defines a TCP, the guidance fails to show how it should stand separate from other historic places, resulting in a false dichotomy. This dichotomy results in separate guidance, separate terminology, and potentially separate rules for a construct that does not exist in law or regulation. The immediate answer is to update 36CFR60 to be more in tune with the intent and ever evolving understanding of the National Historic Preservation Act. Improving the range and diversity of historic places that are recognized by our Nation is a good goal. The proposed guidance does not help.

Background

On November 6, 2023, the National Park Service created a draft, titled: National Register Bulletin: Identifying, Evaluating, and Documenting Traditional Cultural Places, which was issued for public comment on January 25, 2024 (hereafter referred to as the draft Guidance). Comments are due March 25, 2024. The draft and information for providing comment are located in the Federal Register, Volume 89(17):4988-4989.

This draft is a substantial revision to the current Bulletin 38, which was issued in 1990 and last revised in 1998. The current guidance is 24 pages. The draft Guidance is 138 pages, which reflects substantial changes, not just document creep. The draft Guidance represents the best efforts of the NPS team to advise National Register of Historic Places preparers in nominating historic properties that would fall under the aegis of Traditional Cultural Places.

No Regulatory Relief?!

In 1981, the National Park Service developed 36CFR60 to regulate the National Register process. Except for a 1983 tweak, they have been largely unchanged. In 1992, the National Historic Preservation Act was amended. Most notably, it emphasized the importance of Tribal historic places in the National Register, noting that “Property of traditional religious and cultural importance to an Indian tribe or Native Hawaiian organization may be determined to be eligible for inclusion on the National Register.” (§ 302706[a]). The 1992 revisions also directed NPS to “establish a program and promulgate regulations to assist Indian tribes in preserving their historic property.” (§ 302701[a]). This would imply that NPS would need to revisit and probably revise its implementing regulations in effect at the time, including 36CFR60. Although 36CFR800 has been revised numerous times since 1992, 36CFR60 has not.

NPS issued Bulletin 38 in 1990, prior to these legislative changes, but by 1993 (CRM Vol.16 Special Issue), it was clear that traditional cultural properties as defined in the Bulletin, would do the heavy lifting to implement the 1992 amendments. Ultimately there was no call for the need to revise 36CFR60. The regs were OK; Bulletin 38 could clean up the discrepancies in culture and world view.

What is the issue? One should well ask how Tribes are to use regulations that are essentially non-responsive to the kinds of places that are of traditional religious and cultural importance? For anyone who has read the National Conference of State Historic Preservation Officers (NCSHPO) report, Recommendations for Improving the Recognition of Historic Properties of Importance to All Americans, issued in 2023 (referred hereafter as the NHDAC Report), this should not be a surprise. Specifically, the Policy Subcommittee, tackling Legal and Regulatory Issues, identified Traditional Cultural Properties* as the third of three key issues, noting “The current existing structure of the NRHP program does not adequately account for Traditional Cultural Properties (TCPs) and other places of significance to tribes and other communities.” While the report emphasizes the current nature of SHPO and state historic review board involvement in evaluating Traditional Cultural Places, the problem is rooted in the laws and regulations that establish the National Register of Historic Places.

*Please note that the use of the term Traditional Cultural Property is limited to specific citations in previous reports and documents. Otherwise, the term Traditional Cultural Place is used.

TCP’s versus “Normal” Historic Places

The draft Guidance begins by defining a TCP.

A traditional cultural place (TCP) is a building, structure, object, site, or district that may be listed or eligible for listing in the National Register for its significance to a living community because of its association with cultural beliefs, customs, or practices that are rooted in the community’s history and that are important in maintaining the community’s cultural identity.

OK, what is a living community?

A “living community” in the context of a National Register traditional cultural place is a group that is deeply rooted in American history. It is a group that has contributed to the diversity and richness of the American people and the broad patterns of the nation’s history, and that is differentiated from other types of affiliations by its traditional group identity.

OK, a living community is not a family, nor is it a bowling league. Fine.

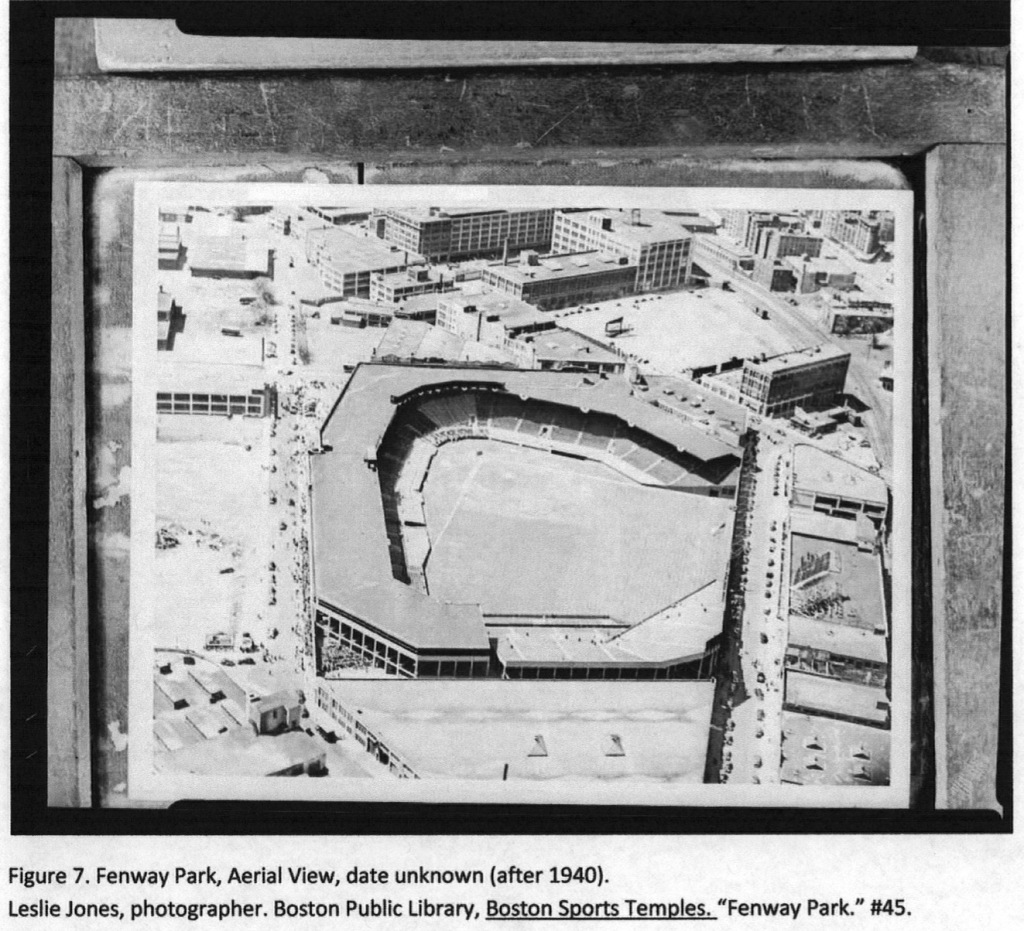

I think the draft Guidance has set up a dichotomy between TCPs and other historic places that may not be real. Let’s take Fenway Park. Listed in 2012, the nominators took pains to declare it was not a traditional cultural place. Throughout the nomination are references to exactly the characteristics that are attributed to a TCP. If you would argue that Red Sox Nation is not a defined ethnic group, I would wholly agree. But then the draft Guidance also notes that the Green River Drift Trail, Wyoming is a TCP, not associated with an ethnic group. Cowboy culture, perhaps? The differences are starting to blur.

In a fashion, all places on the National Register are traditional cultural properties. Think about why they are listed, and hold that thought when going through the draft Guidance characteristics of a TCP (p.27):

To be listed or eligible for listing in the National Register, a traditional cultural place will have the following characteristics:

- The place must be associated with and valued by a living community.

Aren’t all National Register places valued by a living community, whether it be local, state, or national? Going to the NHPA, it states:

… (b) The Congress finds and declares that—

(1) the spirit and direction of the Nation are founded upon and reflected in its historic heritage;

(2) the historical and cultural foundations of the Nation should be preserved as a living part of our community life and development in order to give a sense of orientation to the American people;…

…(4) the preservation of this irreplaceable heritage is in the public interest so that its vital legacy of cultural, educational, aesthetic, inspirational, economic, and energy benefits will be maintained and enriched for future generations of Americans; (my emphasis)

As reflected in the National Register, the NHPA succinctly lays out the need and value of historic places to the American people, and not just to the old blue haired ladies in the DAR.

Next characteristic:

- The community that values the place must have existed historically and continue to exist in the present.

How and why does a historic place get nominated to the National Register? Of course the place has to exist in space and time. But someone somewhere had to take note of it and care about it. On my worst days, I might concede that the National Register exists only to provide developers with tax credits and they may or may not have any historical connection to the place; however, even when a place is nominated by a developer, it’s success in being listed depends much more on the local community’s feelings and their sense of place.

Next characteristics:

- The community must share beliefs, customs, or practices that are rooted in its history and held or practiced in the present.

- These shared beliefs, customs, or practices must be important in continuing the cultural identity and values of the community.

- The community must have transmitted or passed down the shared beliefs, customs, or practices, including but not limited to through spoken or written word, images, or practice.

These three points are really one point. A historic place is the physical expression of a community’s history. And what is the point of history if not to reify the shared beliefs of a community. History is rooted in story. It’s not simply the recitation of facts and dates. We tell our history to tell our origin stories and to answer the question, “who are we?” It is probably one of the essential ingredients that make us human. If I say the words, “Plymouth Rock,” how is it that so many of us know exactly what I’m talking about. Even at the local level, we point to the old school, the mill ruins, or the oldest house in town to remind ourselves of who is our community. And in the age of hyper-mobility, we take our new neighbors and drag them to the library exhibit, the local fourth grade history project, or to the local bar to regale them about what and who they’ve parachuted into and who they should/will become.

Next characteristics:

- These shared beliefs, customs, or practices must be associated with a tangible place.

- The place must meet the criteria for listing in the National Register of Historic Places:

- A place must have significance: it must be important in a community’s history, architecture, archeology, engineering, or culture.

- A place must have integrity: it must retain the ability to convey its significance.

This goes without saying and again applies to all historic places. Finally, the list concludes:

If a place does not have these characteristics, it may not be a TCP as that term is defined by the National Register Program

TCP does not exist in Federal Law or Regulation. More than anything, it is a construct, a tool, really a thought experiment. The TCP is intended to create space for historic places not normally or typically seen as eligible for the National Register. If these are the characteristics that define a TCP, I am hard pressed to see how any NR listed place fails to meet these characteristics. The guidance, going back to 1990, has created a dichotomy between “normal” historic places and “traditional cultural properties.” I do not see that dichotomy.

I think we could all agree that expanding the thinking about the National Register is a good thing. But does it help to create two kinds of historic places that ultimately can only be one?

Who Gets the Call?

The draft Guidance makes an effort to push consultation with traditional communities, including Tribes, and includes a section on Engaging with Traditional Communities (p.41-45), as well as a later section on Reconciling Sources (p. 49-50), which also provides fairly plain potatoes guidance on how to talk and listen. This is all well and good, but… when all the talking and listening is concluded, who gets to say what is or is not eligible for listing? Yes, of course, it is the Keeper of the National Register, but when things are going right, the nomination is teed up for them to give a big yes. When things are going right, all the work is done down below.

The NHDAC report hits it on the head in the Executive Summary:

Tribal sovereignty is more than slighted in the process – they should not have to depend on the state and local decision-making gauntlet to reach the federal government to conduct Government to Government consultation. At the same time, state, local and private property rights and interests require due process considerations setting up an awkward regulatory conundrum. (p. 3)

In 2016, the NHPA was amended to require SHPO review for nominations submitted by a Federal Agency. If there is a THPO present to review a nomination on Tribal land, the SHPO does not have to be involved. However, there are many potential nominations off Tribal land that would qualify as a TCP. If there is no THPO present and authorized, these and other Federally originated nominations must be reviewed by the SHPO. It becomes sticky when a Tribe wishes to make a nomination and expects government-to-government consultation over that nomination, i.e., specifically with the Keeper of the National Register, but there are non-Federal actors in the way, i.e., the SHPO.

Within the draft Guidance, in the aforementioned sections, there is encouragement to engage, but the Guidance is largely moot on the point of who gets the call. Within the current 36CFR60, other than through THPO’s when they have the authority to review, it is the State Historic Preservation Boards and the SHPO that are the arbiters of what goes forth and what is held back. This is despite the NPHA’s language to help Tribes in their preservation efforts, e.g. Sections 302701 and 306131(b).

The draft Guidance becomes especially tricky when advising on Reconciling Sources, where there are discrepancies in sources. Although it does promote talking and listening from the range of available sources, the draft Guidance is still bound by language of 36CFR60.6(k)

Nominations approved by the State Review Board and comments received are then reviewed by the State Historic Preservation Officer and if he or she finds the nominations to be adequately documented and technically, professionally, and procedurally correct and sufficient and in conformance with National Register criteria for evaluation (my emphasis)

What does “adequately documented and technically, professionally, and procedurally correct and sufficient and in conformance with National Register criteria for evaluation” actually mean? The draft Guidance is moot.

Different Rules for TCPs?

At times, it seems the draft Guidance is making up a different set of rules for TCPs versus “normal” historic places. If you look closely, it seems that the draft Guidance is running as close to the line as it can without crossing it, so the charge may be more perception than reality. But the point of guidance is to beat perception into tiny little bits.

Let’s start with boundaries. The draft Guidance states outright that boundaries may be difficult to define and express in European American terms (p.98). The draft Guidance suggests that character defining features of setting may extend beyond the boundaries of the place into the surrounding environment (p.101). They refer to NR Bulletin 16a, but that particular Guidance states that

“The area to be registered should be large enough to include all historic features of the property, but should not include “buffer zones” or acreage not directly contributing to the significance of the property.” (p.56)

For large natural landscapes, the draft Guidance suggests that it may be impossible to agree on boundaries, but since boundaries have to be set, the preparer may need to just forge on (p.113), with appropriate disclaimers (p.116).

Moving on to period of significance, in Section V, the draft Guidance notes that “establishing and expressing the place’s period of significance in European American terms may be difficult” (p.97). Guidance is given by a series of specific examples, which in context for each historic places makes logical sense. Clearly, for some communities, a historic places has always been significant. There is no meaningful start or end date.

When you get to Bulletin 16A, the story changes. The Guidance is fairly clearcut. For periods in history, enter one year or a continuous span of years, e.g. 1928, or, 1875-1888. For periods in prehistory, enter the range of time by millennia, e.g. 8000 – 6000 B.C. Spirit Mountain’s period of significance of creation to the present makes logical sense, but doesn’t conform to Bulletin 16A Guidance.

Is this a problem? The NHPA orders the Secretary of the Interior to promulgate regulations for establishing criteria for properties to be included on the National Register (§ 302103(1)) and for establishing a uniform process and standards (my emphasis) for documenting historic property by public agencies and private parties for purposes of incorporation into, or complementing, the national historical architectural and engineering records in the Library of Congress (§ 302107(2)). The draft Guidance seems to set up one set of rules for TCPs and another set of rules for the rest. Whether the draft Guidance crossed the line or came close to crossing the line doesn’t really matter. Guidance should be clarifying, not leading to further questions.

Boundaries and dates may be an issue of “po-tae-to” “po-tah-to” for the National Register, but these can be huge for applying Section 106 and establishing effects. For better or worse (and too often worse), the National Register exists in a Western legal system, as do all of the land rights. To the degree that Section 106 has value, it is within that system, and so Federal Agencies and those seeking Federal funds or permits examine their undertakings through that lens and no other. For better and worse, land managing agencies must know what is within their responsibilities and what is not. And even though there may be interpretation in assessing effect on an eligible or listed place, there is less leeway in assessing use in 4(f).

TCPs and Religion

36CFR60.4 is abundantly clear.

“Ordinarily…properties owned by religious institutions or used for religious purposes…shall not be considered eligible for the National Register.” “However, such properties will qualify if they are integral parts of districts that do meet the criteria of if they fall within the following categories:.. A religious property deriving primary significance from architectural or artistic distinction or historical importance…”

This does not leave much wiggle room for historic places such as Inyan Kara Mountain, in Wyoming. The solution in the draft Guidance is to somehow excise religion from Lakota culture and cosmology. What remains is the home of spirits in the traditions of the Lakota and Cheyenne (p.72). Likewise with Kootenai Falls in Idaho, now properly cleaned up as a vision questing site. My question is why or how would you be able to remove religion from a traditional culture?

The draft Guidance states

Criterion Consideration A was included among the National Register Criteria for Evaluation to avoid historic significance being determined on the basis of religious doctrine, not to exclude any place having religious associations. (p. 70)

I think this is only part of the story. Separation of church and state was on everyone’s minds in 1966. Criterion Consideration A was put in to specifically exclude religious places. (see Cushman 1993:50). Otherwise the first 500 nominations to the NR would have been churches, synagogues, and mosques of various denominations. A traditional cultural community might have a religion that looks different from monotheistic Christianity, but religion may and often is fully integrated into the culture and no easier to separate out than extracting the ghosts of Ted Williams, Babe Ruth, and Carl Yastrzemski from Fenway Park. For many TCP’s to be eligible for listing and needing Criterion Consideration A, the entire culture would need to have religious and spiritual values excised. To paraphrase Richard Henry Pratt, “Kill the religion and save the nomination.” This is yet another reason why 36CFR60 needs revision.

Where to Go From Here?

I feel bad for the authors of the draft Guidance, as they have been given a bad hand to play, and try to play it the best way they can. For those of us who write guidance and policy, the frame, the language, the content- all of it has to be tied to both law and regulation. This is Guidance 101. We are not allowed to just make stuff up. The problem with the draft Guidance is that is built on a foundation of mud and the pilings don’t reach the bottom.

The highest priority should be to revise 36CFR60 to accommodate historic places that don’t fit in the Western Cultural paradigm. This was recommended by the NHDAC. Their recommendation is still valid. I wonder whether the resources spent on drafting this Guidance wouldn’t have been better utilized in updating the regulations.

Pending revisions to the regulations, one must question the utility of the TCP construct. It doesn’t exist in the NHPA nor in 36CFR60. It doesn’t exist in Bulletin 15, except by pointing to Bulletin 38. Likewise with Bulletin 16A. It’s not in Form 10-900. TCP has its genesis in 1990 as a response to the American Indian Religious Freedom Act and the 1983 Cultural Conservation Report submitted to the President and Congress. The intent of the TCP was to broaden the thinking of the National Register, to nominate and list historic places of value to traditional communities, not just Independence Hall and Plymouth Rock. The creation of the TCP also created a problem. TCP’s have to meet the National Register standards, as outlined in 36CFR60 (see above), so although they may be visible as this different thing, legally it is all of single piece.

Without TCP legal and regulatory standing, the preparers of this and earlier Guidance have to navigate what is special and what is the same. This is not a good place to begin writing guidance.

Compounding the difficulties in this draft (as well as the original 1990 Guidance), the argument starts with the premise of “here is the norm, now let’s talk about what’s different as an exception to the norm.” I believe that was a mistake, in that it unintentionally elevates the norm to, uh, the norm and the TCP as some to be handled by exception. My own experience of working with the National Register in one way or another over the last 40 years is the ability for the NR as well as the National Historic Preservation Act to grow and evolve generally within existing law. Keeping in mind the NHPA begins:

… (b) The Congress finds and declares that—

(1) the spirit and direction of the Nation are founded upon and reflected in its historic heritage;

(2) the historical and cultural foundations of the Nation should be preserved as a living part of our community life and development in order to give a sense of orientation to the American people;

(3) historic properties significant to the Nation’s heritage are being lost or substantially altered, often inadvertently, with increasing frequency;

(4) the preservation of this irreplaceable heritage is in the public interest so that its vital legacy of cultural, educational, aesthetic, inspirational, economic, and energy benefits will be maintained and enriched for future generations of Americans;

Nothing in this limits what the Nation finds as its historic heritage. Instead of beginning with the norm and providing guidance for the TCP, maybe the guidance should begin how so-called normal historic places have their own cultural roots and how their presence on the National Register owes to traditional communities, such as the DAR or the Mount Vernon Ladies Association, and how Red Sox Nation can be considered a religion and Fenway Park a religious property. The guidance could and should talk more of a continuum of cultural communities within the larger Nation and less about a binary of differences.

The current draft Guidance should be withdrawn. Overdue work should begin on revising 36CFR60, with an eye toward expanding our thinking on what can be eligible for listing in the National Register. Out of that thinking, it may be reasonable and proper to retire the TCP construct and to think of all historic places as tied to their own traditional communities.

Citations

National Conference of State Historic Preservation Officers

2023 Recommendations for Improving the Recognition of Historic Properties of Importance to All Americans. A Report of the National Historic Designation Advisory Committee.

National Park Service

1983 Cultural conservation : the protection of cultural heritage in the United States : a study by the American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, carried out in cooperation with the National Park Service, Department of the Interior ; coordinated by Ormond H. Loomis.

1992 Guidelines for Evaluating and Documenting Traditional Cultural Properties. Bulletin 38

1993 Traditional Cultural Properties. CRM Volume 16, Special Issue.

1995 How to Apply the National Register Criteria for Evaluation. Bulletin 15

1997 How to Complete the National Register Form. Bulletin 16A

2012 Fenway Park National Register Nomination. NAID 63796726