The views expressed here are entirely my own and do not represent any other group or organization.

At 3:05 PM on March 12, 2019, I received a disturbing e-mail from our Society for American Archaeology President, Susan Chandler.

SAA is aware of the disheartening termination of archaeological staff at the University of Kentucky. We have released a statement, available on our website, and sent emails directly to the University of Kentucky President, Provost, Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, and Anthropology Chair. If you have a connection to the University, the Kentucky Archaeology Survey, or the Program for Archaeological Research, please consider also sharing your experiences.

I knew some of the staff in the UK Archaeology Survey. My recent experience working with Indiana University of Pennsylvania suggested something was odorous. Over the next few days, I took to my pen and dashed off a letter to the editor of the Lexington paper and a smidge more civil letter to the Dean of the UK College of Arts and Sciences. It made me feel good, but had no effect whatsoever. The News-Gazette did not run the letter and I received a canned response from the University, saying in effect, “We got this. Butt out.”

My indignant and ultimately useless letter to the editor of the Lexington News-Gazette, dated March 14th:

UK’s Plan to reorganize with William S. Webb Museum by eliminating the Kentucky Archaeological Survey is misguided and harmful to the citizens of Kentucky. For more than 20 years, KAS has provided its students with hands-on experience in Kentucky archaeology. KAS brought new finds to the public and assisted state agencies and numerous local nonprofits in carrying out their missions. KAS has saved taxpayers money and helped these organizations save the past for the future.

Land grant universities have a special responsibility to its citizens, to improve lives through excellence in education, research and creative work. Shortly, UK will be walking away from a program that does all of this. As a resident of Pennsylvania, I can tell you what your future holds. Pennsylvania’s land grant university abandoned its role in Pennsylvania archaeology 30 years ago. Its anthropology department now studies every place on the globe except ours and every people except Native Americans. As a practicing archaeologist, I can tell you now that any promises made by UK regarding the new research program for your history and heritage will be empty promises. And as someone who built partnerships between state agencies and universities that care about their public charge, I can tell you that Kentucky will be poorer for the change, both financially and in its heritage. William S. Webb spent his life working with TVA and the Civil Works Administration to bring Kentucky’s past to its residents. He would be appalled.

Some of us had various theories as to why this mowing had taken place, but I had my own ideas, as it brought flashbacks of my old, dear Alma Mater, Penn State University. UK was not acting irrationally within its own paradigm, its own bubble, which can be summarized as, “Research good. Cultural resource management bad.” This is the same sentiment as encountered at good, old State.

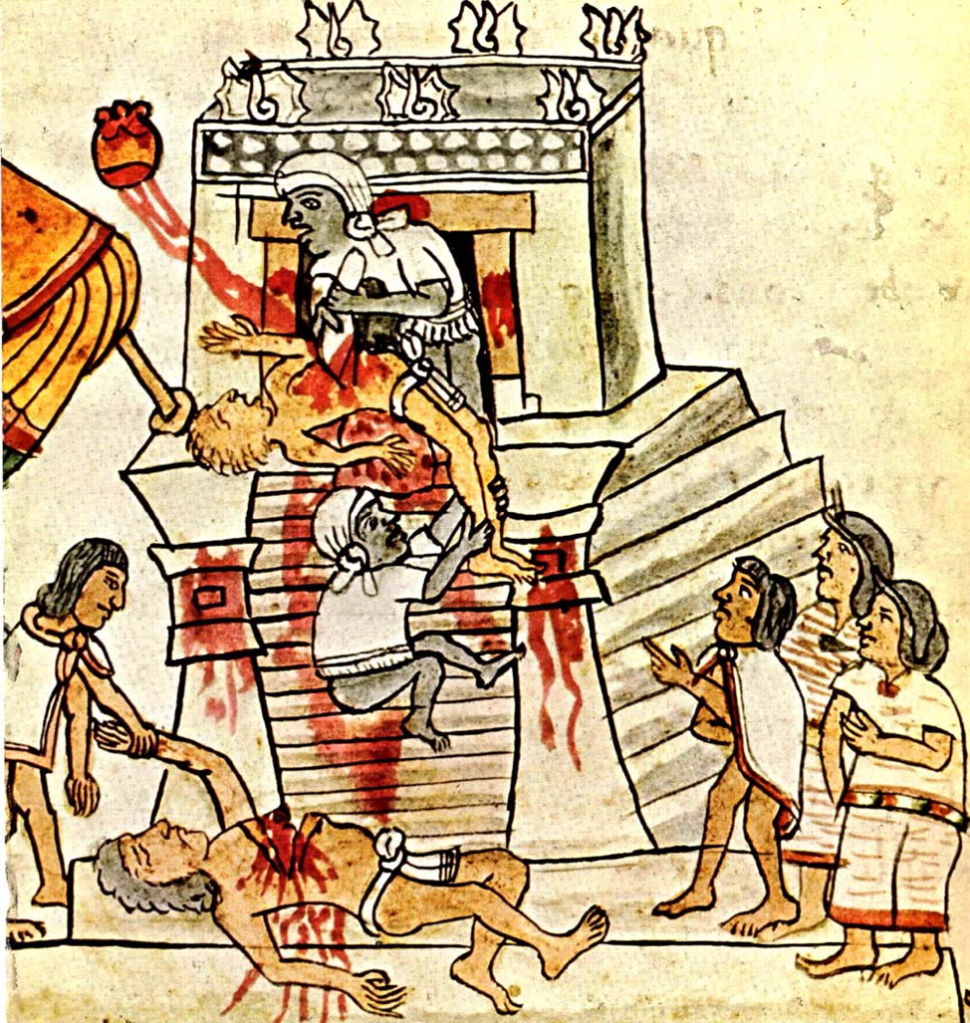

In the interest of full disclosure, I received my Master’s and Doctorate from Penn State, graduating in 1986. I had some fine professors, including James Hatch, who did not share the same disdain for practical research as some of his peers. I came to Penn State with a focus on Mesoamerican archaeology and an interest in state formation, two research areas I picked up while an undergraduate at Rice University, under Rich Blanton, Gregory A. Johnson, and Frank Hole then later at CUNY, Hunter College under Blanton and Johnson again. However, during the middle of my first year, I grew more interested in North America and the formation of ranked societies after discovering Lewis Henry Morgan.

I received a first rate education from Penn State from a group of fine professors who emphasized the 3- or 4-field approach to anthropological archaeology. They prepared me not one whit for my first and second real jobs, working for the Maryland Geological Survey and then at PennDOT, managing cultural resources programs that included archaeology. It was OJT all the way, learning one mistake at a time. At meetings, when encountering one of said professors, they uniformly gave me the same look a dog owner gives to a puppy that missed the paper.

I have a hard time disliking the professors* that poured knowledge into my head, especially with regard to cultural ecology. But over a career of 40 years, I have grown to feel that their biases against practical research were not only misguided, but harmful. The second issue I had with the Penn State Faculty (James Hatch partially excused) was a complete disdain for Pennsylvania archaeology. As Penn State is a land grant institution, and still the premier university in the Commonwealth, and still a recipient of at least some state aid, I find this lack of interest damning.

*with respect to academics and not some of their other behaviors

One incident should make my case. A few years ago, while at PennDOT, we had a vexing problem with one of our enhancement projects, a bike trail. It turns out the bike trail would adversely impact a significant archaeological site and there was really no way to design around it. A data recovery was called for, but the sponsor, in this case College Township in Center County, PA, had not budgeted for the extra work required to get these federal funds. Whether they had budgeted or not wouldn’t have made any difference as the cost of the archaeology would have been several times the total cost of the project and would have thus killed it in its crib.

We thrashed around for a solution for some time, but since the project was on the Penn State Campus, we decided to approach the Anthropology Department to see if they could mitigate the archaeological site that was on their campus for a project that would benefit mostly their students. After all, that’s where the archaeologists are. With a field school on campus, they could have had their cup of coffee and gotten in a few units before the first cigarette. WE WERE LAUGHED OUT OF THE ROOM!

Ultimately, we were able to arrange for Juniata College to do the same field school on the Penn State Campus for College Township benefit, and the project won a Governor’s Award for partnerships (but not with Penn State).

Which brings me to the trigger for this post, and it was not the University of Kentucky debacle. George R. Milner, a professor of anthropology at Penn State, was recently elected to the National Academy of Sciences. He has had a distinguished career at Penn State, the PSU press release noting 10 books, a hundred articles, service on numerous boards, and membership as a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Chopped liver, he is not.

However, in perusing his long curriculum vitae, in over 24 pages of single spaced entries for publications and meetings papers, he has exactly one presented paper on the subject of Pennsylvania archaeology, in 1996, and one book review, in press. No field work conducted in Pennsylvania, and not one graduate student who made Pennsylvania the subject of their thesis. It’s not nothing, but as close to nothing as you could get in a long and broad career at University Park, Pennsylvania.

I don’t know Dr. Milner well. We are not friends, barely acquaintances, and this is not a knock on his career or distinguishedness. His election to NAS speaks for itself. I have no reason to doubt he is a good person. But I do believe he is a symptom of a bigger problem that is rooted in hiring decisions at the “University” and reward criteria at the “Academy.” Until these are changed, the Dr. Milners of the world will continue to be nourished and rewarded, and the basic precepts of where and why to conduct archaeology will remain unchallenged.

At the Society for American Archaeology Meetings in April in Albuquerque, there was a side meeting of some very smart and very well meaning archaeologists representing the Coalition for Archaeological Synthesis.

The Coalition for Archaeological Synthesis (CfAS) promotes and funds innovative, collaborative synthetic research that rapidly advances our understanding of the past in ways that contribute to solutions to contemporary problems, for the benefit of society in all its diversity. This is accomplished through the analysis and synthesis of existing archaeological and associated data from multiple cultures, at multiple spatial and temporal scales.

Coalition for Archaeological Synthesis: http://archsynth.org

Basically, these are archaeologists who think that the field can actually do something to better the world, especially if done together with other scientists. It is a worthy project that shows how archaeology actually adds value to collaborative problem solving, given that we can see the world broadly and through a ridiculously long time period. The subtext of the concept is that archeology is usually under attack as a field of study and that we all need to up our game to stick around.

Sitting here in Pennsylvania, far removed from the Annual Meeting, and only freshly removed from the State Meeting, I wonder if we are up to the job. After all, the State Meeting started yet another scrum over where the Monongahela Peoples came from and where they went. We are still working out basic chronology and culture history stuff here, let alone evolution and culture change. It’s been this way as long as I’ve been in Pennsylvania and I suspect it will continue for a while.

And why would this be so? Are the archaeologists that study Pennsylvania particularly stupid? I doubt it. Are they not trying hard enough? Don’t think that’s the problem. Is Pennsylvania such a backwater that there’s nothing worth studying here anyway? Lewis Henry Morgan didn’t think so and neither do I. What is missing from here that is not missing out in the Southwest (besides beautiful pueblo dwellings)?

My own theory stems from a brief discussion carried on during the CfAS meeting, specifically dealing with finding a permanent home for the CfAS institution, in other words giving it a place to be. The leaders of the discussion rattled off a number of premier archaeological research institutions. Penn State was not among them, not because they aren’t a premier research institution, but because the archaeologists there do not have a stake in the prehistory of their turf nor a desire to raise the flag for applied research to solve real problems. Note that this is not the case a few buildings down from Carpenter on the University Park Campus, where the College of Earth and Mineral Sciences has just established a dual title doctoral degree program in Climate Science. Thank you, Michael Mann.

Of course, I’m picking on Penn State and Dr. Milner. They are easy and familiar targets. The problem is much, much deeper. Going back 100 years, what higher educational institution has committed to a long-term program of research into the prehistory and archaeology of Pennsylvania? All of the heavy lifting had been undertaken by Museums, specifically the Pennsylvania Historical Commission and later the State Museum, and the Carnegie Museum. This is the quintessential early 20thcentury model – prior to the era of university trained archaeologists, the museums took the lead. Every so often, there is a flash of interest at a local university, which lasts a generation (one professor), then fades. Mostly state schools, by the way, and Temple occasionally, but not currently. The heavy hitters – Pitt, Penn State, Temple, Penn– are absent from the field of battle and have been absent since day 1. The long-term institutional commitment has simply not been there. Whether this is a chance artifact of history, it’s hard to say, but it still influences everything done today. This is critical, since real archaeological progress is expensive, requires people, not just one scientist, and long-term commitment from the administration, and I mean long-term by archaeological standards, not 2-3 years.

The future of American Archaeology is not pretty, despite recent advances in technology and DNA. Universities are churning out PhDs in record numbers despite a shrinking job market. The only field that has shown stability, if not growth, has been in cultural resources management, but most programs do not prepare their students for careers there. That was the case in 1986, when I got out, and sadly is the case 30 years later. The arms race in academic research rewards the exotic, the sexy, the new, not basic knowledge building and certainly not local prehistory. Students do not get the important hands-on practice that professional archaeology demands. I have hired my share of staff archaeologists. It is shocking the number of highly educated PhD’s I have reviewed and interviewed who are unable to perform the basic duties of the job.

The bottom line is that the hiring decisions by universities and the reward systems for tenure and recognition need to change radically. Local archaeology needs to be given the same respect as the highlands of some distant land. Cultural resources management needs to be the integral part of training for the jobs that will be out there.

Of course, all of this can be laid at the feet of Abraham Lincoln. He created the Land Grant Universities in 1862, but forgot to give them courage. He created the National Academy of Sciences in 1863, but forgot to give it a heart. The university administrators of the world appear to operate without a brain among them. The Imperial Wizard would be appalled.

The Penn State Alma Mater

by Fred Lewis Pattee

For the glory of old State,

For her founders strong and great,

For the future that we wait,

Raise the song, raise the song.

Sing our love and loyalty,

Sing our hopes that, bright and free,

Rest, O Mother dear, with thee,

All with thee, all with thee.

(Softly)

When we stood at childhood’s gate,

Shapeless in the hands of fate,

Thou didst mold us, dear old State,

Dear old State, dear old State.

(Louder)

May no act of ours bring shame

To one heart that loves thy name,

May our lives but swell thy fame,

Dear old State, dear old State.