Last month at the SAA Meetings in Denver, the Society took a much-needed break from the never-ending chaos of the current Administration’s war on history and science to continue the Airlie House 2.0 effort. Looking at the goals of this necessary effort, one almost sheds a nostalgic tear for those halcyon days. Whether our profession survives the current onslaught remains to be seen. However, it is wise to prepare for the time after. While this is not our version of Project 2028, for now it’s the best game in town.

The Thursday morning session was well attended, but under the circumstances I would have liked an overflowing room. Here is the Session abstract.

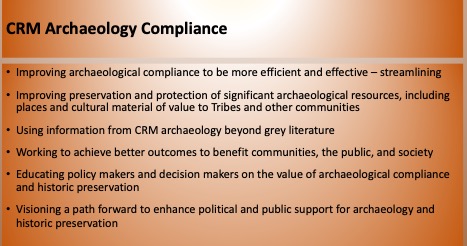

Session Abstract

The passage of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 and both the culmination of a series of topical Airlie House seminars in 1974 and the culminating 1977 Airlie House Report set the course of cultural resource management (CRM) archaeology in the United States for the next 50 years. Now, 50 years later, the profession is transforming, guided by newer and amended laws and regulations, technological innovations, a curation crisis, and social issues such as climate change, environmental justice, and the rights of descendant communities. These changes are affecting how CRM archaeology is practiced, and, in recognition, a workshop sponsored by the Society for American Archaeology (SAA) and National Park Service was held in May 2024 in West Virginia. The workshop drew on the expertise of professionals nationwide and considered four major issues selected by SAA membership that will affect CRM archaeology in the coming decades. This SAA forum will summarize the major topics discussed and recommended action items proposed by the Airlie House 2.0 workshop, which, if implemented, will affect our profession in the coming decades. Membership participation in this SAA forum and implementing change is expected and welcomed.

After brief comments on the various themes from the discussants – Rebecca Hawkins, Karen Mudar, Alex Barker, and Signe Snortland, as well as moderator Kimball Banks – the floor was opened for questions and comments. My impression from the Session was that the SAA was moving methodically on this, not rushing, and willing to review and revisit any and all positions.

When the SAA solicited for comments a year ago April, I took the opportunity to weigh in, but did not post my comments on my blog or anywhere else publicly. The SAA reached out to its membership with a status report last October.

In retrospect and taking in all that happened in Denver that week, I am sharing my comments below. Most still seem relevant a year later, but where appropriate I am annotating – commenting on my comments, as it were. Slides were provided by SAA in 2024.

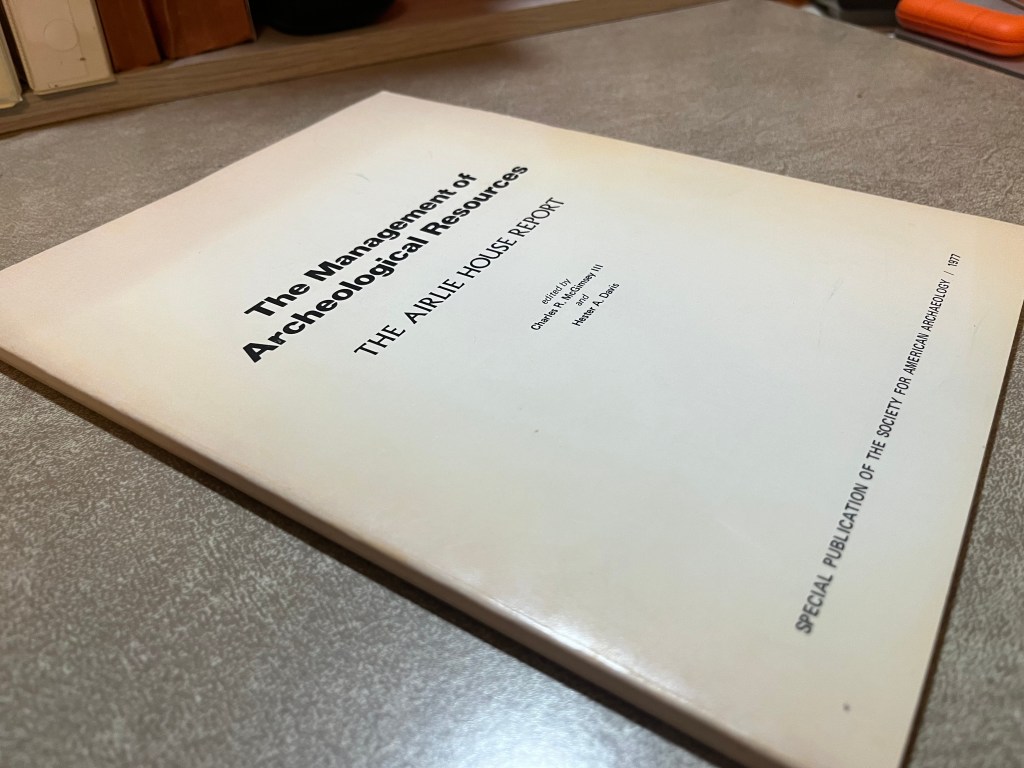

Workforce Training and Careers

It has been my long experience in a career in cultural resources management that everything starts and ends with a trained an motivated workforce, so it is fitting to begin here.

There are a couple of premises that I hold to be true and that drive the discussion with regard to the question, “How do you build an archaeologist?”

- The very first thing to know is that archaeology is both a profession and a trade. You cannot build a good archeologist from the classroom only. Remember the term, “armchair archaeologist?” Likewise someone very good in the field, unless a true savant, cannot have the grounding and theory and method gained from a classroom education to be truly useful. It takes both education (the professional side) and experience (the trade side).

- The current model of getting an undergraduate education in anthropology and then graduate school with a field school somewhere in there and then starting as a field crew member and working your way up to Principal Investigator is suitable for a small fraction of potential archaeologists.

- It takes too long. Eight years, if you include 4 years of undergraduate, 2 years of graduate and then 2 years of practical experience.

- It costs too much for the return. College is no longer affordable and even PI salaries aren’t sufficient to cover the up-front costs.

- It effectively blocks all but those with resourced families that can support this ascent. And this plays into the racial disparities in familial wealth. It is possible this alone could explain why archaeology is such a “white” profession.

- This also disregards the inherent bias against compliance archaeology by the mainline university graduate programs, who continue to train Mesoamerican archeologists or any other cultural region other than the US, who have no useful education or training that would prepare them for a CRM career. More on that later.

- There is a lot of talk about alternative pathways to building an archaeologist and I think this discussion is worthwhile. However, it is also treacherous insofar as any who wants to pursue this alternative pathway needs a clear understanding of what are the consequences of veering away from the traditional model, codified in the Secretary of Interior Standards.

- SOI standards are at the minimum, a standard. And generally, they can be applied to an individual to determine whether that individual can meet that standard.

- Once you agree that there can be an alternative pathway, it is essential that there be national agreement on what is required within that pathway. And the more flexibility you give in that pathway, the more urgent the need to settle on a national standard of competence.

- For any student seeking to become that professional archaeologist along this alternative pathway, there has to be a clear plan, i.e., what exactly they need to know and do to get there. Part of the attraction to establishing an alternative pathway is two-fold: less classroom and more OJT meaning less cost and time, and, more ways for entry from a different career. Choices come with costs. It is inexcusable to tempt a potential candidate with an alternative and have them spinning their wheels because the specific requirements weren’t specific enough. They think they are making progress toward that brass ring, but are actually veering off into the weeds.

- If there is an alternative pathway, there has to be some adjudicating group that will certify that the candidate has indeed gotten there and meets those standards. The more flexibility you give in getting to professional qualifications, the more important this becomes. For geologists or engineers, there are state boards that certify candidates professionally. Buttressing these boards is an infrastructure of standards, training, and testing, not to mention legal licensing.

- Finally, you can’t put dead ends into the mix, meaning you cannot offer a progression from a field-based experience to a Crew Chief and then offer no way to advance to PI other than the traditional approach. There may be individuals that don’t want to become Professional Archaeologists but want to remain as highly skilled technical workers, but for those that want to advance to Professional status, there has to be a non-traditional route to get there, from each stage of accomplishment.

- SOI standards have a gaping hole. They do not require any knowledge of historic preservation law or practice, such as Section 106, or NEPA, nor frankly anything to do with consultation with groups that have interests in the projects, such as Native Americans. This needs to be addressed somewhere in the standards we would adopt.

Focusing on the traditional method of getting to professional status, there are several things that can be done to lessen the time required and lessen the economic burden.

- If we’ve learned anything since COVID it is that there is a useful role for remote learning. This was experimented through MOOC classes a decade ago, but we now know what we can teach remotely and what we cannot.

- I would argue that any class that was traditionally taught as a survey in a large classroom is a prime candidate for remote learning. Introduction to Anthropology, Introduction to Cultural Anthropology, Introduction to Archaeology, frankly any course that beings with the phrase “Introduction to….” I am not saying these courses aren’t important, just that they aren’t necessary to take in person in a university setting.

- We are already talking about bringing Community College students into universities as a cost-saving measure and as a pathway to an affordable university education. Many of the courses that a Community College would offer are in the “Introduction to…” realm.

- This is the opportunity for SAA and RPA and maybe a consortium of universities to assemble a core curriculum of introductory on-line courses that can be offered at any time and no cost to anyone. If we can establish this curriculum with regards to minimum requirements, we can wipe a half dozen courses off the schedule, at the very least a full semester. For candidates with day jobs, this should be a godsend.

- Going this route will also require a test of some type to ensure that the candidate has mastered the material. Use the College Board as a model.

The trade aspect of learning is just as important. To that end, the traditional field school is inefficient, expensive, and non-standardized. It may be time to bury the idea entirely.

- Instead, hands-on experience could be gained through a trade union model – apprentice, journeyman, master. This is an opportunity, but there are some caveats:

- In most trades, there is a union that takes responsibility for certifying the skill levels of its members. (When I submitted my comments to SAA in 2024, I was unaware of unionization efforts for archaeological technicians. On Thursday afternoon, I heard a presentation from Freeman Stevenson, titled “The Return of Unions to the CRM Industry,” presented in the US Archaeology at the Crossroads Part I Symposium. The long, hard effort toward unionization appears to be underway with the Teamsters. It remains to be seen if it catches fire. I have no illusions that it will be easy. After all, virtually every effort at unionizing any sector of the economy took decades. Still, Stevenson and others give me hope.)

- In this model, the unions set up off the job training and oversee it. (I confirmed with Stevenson that his efforts include this model of union training, currently housed in West Virginia.)

- Work at any of these levels is paid work, through the terms of the contract. More skill means more pay. Lower level trade members work under the supervision of a higher level. Archaeology has done training in this manner for decades, but we are loathe to call it that, since we are “professionals,” not plumbers. And we either grossly underpay our underlings, or not at all.

- Industry is part and parcel of this arrangement. This is how they get trained workers. They offload the training and certification to the union. Collective bargaining agreements manage the relationship.

- Archaeology could unionize and set up an arrangement for training along these lines. (See comments above.) If they don’t, then following this trade union model (which I believe to be a good model for training), would require setting up some national or regional system for overseeing the training and certifications.

- At the end of the line, there needs to be some certifying organization that would judge candidates, possibly at the levels of crew chief and Principal Investigator/Professional Archaeologist. Standards probably need to be national to allow movement between states. There could be qualifiers for regional expertise built on top of the standards.

I haven’t spoken to some of the education that I consider essential to making a good professional archaeologist. That is coursework in cultural anthropology, especially political anthropology and, yes, anthropology of religion. One of the shortfalls of current archaeological training is the overemphasis on practical field techniques over a strong grounding in anthropology. Especially when working with descendant communities, a good anthropological background is invaluable. In the future archaeological environment, avoiding consultation with descendant communities is a non-starter.

Melding the professional and trade aspects will require some coordination. Schools like Drexel University already incorporate a strong internship practice within their programs. Aggressive merging of on-line classes, OJT, and a trade union model of apprenticeship could reduce the classroom component of professional training to 3-4 years (In my estimation), resulting in a Master’s Degree. Overall, it may take a person the 6-8 years to get there, but they will be fully employed during most of it.

Will the academy go along with this? I doubt it. They haven’t to date and this disrupts their traditional models of education. What I would say for land-grant institutions is this. “Not only have you received your charters from the Federal Government as well as much support, but also have built your institutions on land taken from the Indigenous Peoples that inhabited it earlier. You owe two debts in the telling of the history of this country, one to the public at large, and one to the original inhabitants. Archaeology is one method of telling a history that wasn’t written down or a history only told by the victors. Establishing an archaeology program that doesn’t include the state you are in is simply negligence of duty.” SAA and RPA need to bring the full force of their influence on this point, not just to the university presidents and deans but the state legislatures that fund these institutions.

Is there an impending shortage of archaeologists or not? I keep getting two different answers and I’m not sure everyone is speaking from the same data. Altschul and Klein sounded the alarm 2 years ago in a deep dive of the future for the profession. Yet at the SAA Meetings in NOLA, Chris Dore in Session 293: Transformations in Professional Archaeology, Industry Challenges for Cultural Heritage Consulting Firms in North America, strongly suggested the issue was overblown and there are sufficient archaeologists to meet future demand. Can both views be correct? I have my doubts.

Part of the problem may be on which data each argument rests. Altschul and Klein seem wary of US Bureau of Labor Statistics data as showing the full picture, while Dore seems to rely heavily on that data. Dore also seems to accept that PhD’s generated from the academy will be suited to the CRM world. My own anecdotal surveys show regional unevenness and unevenness in level of archaeologist. Some parts of the country seem to be OK at the moment for supervisory archaeologists but are having trouble getting field crew. Other parts of the county see vice versa or any other combination. So it is hard at the moment to see a national trend, whether there is one or not. Perhaps the biggest difference is that Dore sees work declining in future years, while Altschul and Klein see an explosion shortly. (In any case, the recent wide-spread firings of Federal employees, including archaeologists and the intentional weaking of environmental and historic preservation laws and regulations may resolve the issue simply by eliminating the need for CRM studies, therefore eliminating the jobs.)

My own takeaway from this discussion is that we need to focus on the way we are currently producing archaeologists, which is inefficient, and socio-economically discriminatory. I do believe the issue of field crew will be solved in the market. You have to pay people better to get folks who will work in that environment. Plain and simple. It appears that this is starting to occur, but still there are gaps in matching a “trained” workforce with jobs.

A final thought. Bureau of Labor Statistics grossly underreports archaeology jobs, yet many universities rely on these numbers to gauge future student interest. This is to our detriment. As long as academia has a role in training future archaeologists, and I think they do, putting department after department at risk from dodgy numbers is a bad idea. SAA and RPA need to be united in pushing the Labor Department hard in the direction of producing more accurate counting of the number of working archaeologists in the US. And they need to do this today. Having a certified and licensed category will point BLS in the right direction.

Diversity in the workforce (a good goal, regardless of what the current Administration thinks)

This continues to be a problem, but I do believe the underlying issue is the amount of family wealth needed to “front” a student through the long and expensive process to reach professional status. Otherwise, the student is likely to incur crushing student loan debt. Targeted scholarships and financial aid only goes so far and it probably unsustainable. The only way to create diversity in the workforce is to radically cut the costs in time and money to get to professional status. I have offered some ideas above. People aren’t stupid. You can be welcoming and accommodating ‘til the cows come home, but those economically disadvantaged won’t commit unless they can see a sustainable future in it. And while better pay in the entry level field crew positions can help there, commensurate pay for professionals is also needed, not just in academia but in government and private employment.

Certification and licensing

I have written at some length about certification and licensing. To summarize, we need to keep clear the difference between certification and licensing. Organizations like SAA or RPA or state councils can certify. State or Federal Governments can license. And while I do support certification at a regional level or national level, licensing should be a goal. I think this will help with pay, respect (which translates to pay) especially within the private sector land of engineers, and clarity with regards to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

I think licensing is much more important in cultural resources management than academia, but it wouldn’t hurt to have a segment within academia that are licensed.

Decolonizing-Engaging Descendent Communities

My first recommendation is that the word “decolonization” should be dropped. It is not useful within the context of Airlie House 2.0 and CRM. To me, it sounds like bumper sticker sloganeering. It is designed to offend all but the true believers. It invites the nativists in our country (an exquisitely choice term which really means the opposite of what it appears to mean) to jump down our woke throats and fight anything we might want to accomplish. Even within our group, we will waste a lot of time trying to define what it means and this is time wasted, when effort needs to be focused on doing. (Everything done since January 21st vindicates this statement.)

Almost all CRM archaeology is conducted under Section 106, which is a Federal law administered by federal agencies, which are part of the United States Government. Let me suggest a test. The next time you are in a project meeting with the design team and engineers, just casually suggest that we need to decolonize archaeology. See what the response is.

There was a lot of good advice in the original Airlie House Report, produced in 1977, relevant to this topic. I think most of it has been ignored in the subsequent 47 years. While there has been some advances in law and practice since then, it may be a good idea to start with Section 5: Archaeology and Native Americans, and proceed from there.

If 36CFR800 is the basis for most cultural resources management under Section 106, or Section 110 for federal land management, then the core singular point is this. “As anthropologists, should it not be the archaeologists first responsibility to take into consideration living descendants of those cultures they study?” (their emphasis) (p.90)

There is a special role for consultation with Federally recognized Tribes in conducting compliance archaeology. It is specifically defined in 36CFR800.16

Consultation means the process of seeking, discussing, and considering the views of other participants, and, where feasible, seeking agreement with them regarding matters arising in the section 106 process. The Secretary’s “Standards and Guidelines for Federal Agency Preservation Programs pursuant to the National Historic Preservation Act” provide further guidance on consultation.

Most consultation takes place within a specific project and in that sense is limiting. What is ultimately necessary for effective project consultation is building a trust relationship outside of projects. Many state DOT’s and FHWA divisions have taken that extra step to build a working relationship and I think this is the way to move forward. And it takes respect, humility and hard listening to make it work. The outcomes of these extra-project meetings and consultations can find value in program wide programmatic agreements.

If we can take a wider view of consultation, then some of these other issues will be addressed. We can sit down with the Federally recognized Tribes and figure out how to increase the number and presence of native archaeologists. But we would need to dig deeper and sit down with the Federally recognized Tribes and figure out what are the important questions to ask and what stories to tell. Not on a project by project basis, but within the profession. So ultimately, although this is a CRM exercise, the universities have to be willing to bring representatives from Federal Tribes into discussions of how and what to teach in archaeology. Only then will we be taking into consideration the living descendants of those we study. Hiring one or two indigenous archaeologists to the faculty will not solve this problem, although it’s a good starting point. (See also, Bonnie Pitblado’s 2022 article in American Antiquity 87(3):217-235, On Rehumanizing Pleistocene People of the Western Hemisphere.)

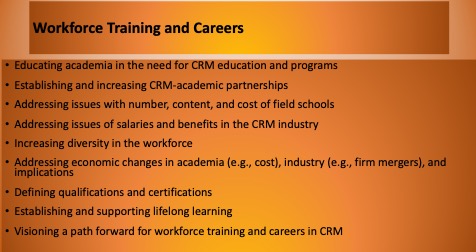

Archaeological Collections, including Records

I don’t have all that much to add to this section, with one exception. There is an inherent problem baked into the CRM process under NEPA. The problem is a contracting and timing problem and is created when project schedules force the conclusions from a study to be produced before the collections are fully processed and designated for accessioning. The NEPA decision depends on the conclusion of Section 106. It is almost always presumed that a draft executive summary serves as the results of Phase I or II investigations. The design consultant and their archaeological team finishes their work, a NEPA decision is made, and then the contracts are closed out as the (obvious) work is completed. However, if there are artifacts, a closed out contract doesn’t allow funds for the archaeological consultant to process or accession them. And there is no obvious hammer to leverage over the consultant since processing the collections is rarely in the punch list of deliverables. How could they, since it might not be completed until after the project is built years later?

Secondly, funding set aside for archaeology in the design stage is finite. It is spent in order – field work, essential lab work, executive summary, final report, artifact processing and curation. Often field work and essential lab work consume the entire budget, so by the time the final report and artifact processing and curation is to be done, there is no funding. Going back to the client and/or prime is out of the question. So the work doesn’t get done.

If there is a data recovery involved in the project, again there can be a contracting problem. First, almost always there is a separate consultant involved due to the conflict of interest provisions related to NEPA. The new consultant often acquires the collections from the Phase I or II and proceeds to Phase III. As before, it may take years for the collections to be fully processed and accessioned and once the project has the ribbon cutting, the contracts are often closed. The total amount needed for curation is a tiny fraction of the total project cost, perhaps $100k versus $100m, so holding the contract open for such a small amount is difficult to sell. Rarely have I seen adequate provisions set in the contract to reserve monies to complete the curation in a Phase III. It’s really hit and miss.

The Federal Agencies are often not much help. Archaeologists are rarely in the room when contracts are drawn up, and few agencies have the archaeological expertise to bring to bear even if someone thought to ask an archaeologist to help in putting the contract together.

Perhaps the only real solution is to set up a bond model for artifact curation, where the contractor puts up a bond solely for the processing of the artifacts and their ultimate curation.

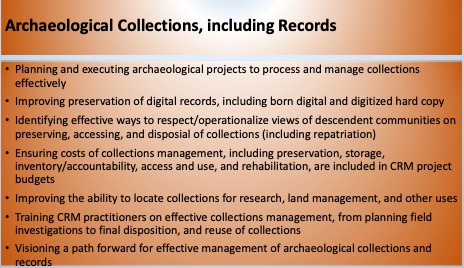

CRM Archaeology Compliance

If we do the necessary work in fuller consultation with Federally recognized Tribes, we should expect to widen the range of questions we would want to ask from the archaeological record and expand and enrich the kind of stories we could tell. If we lay the proper extra-project groundwork, we should also be able to achieve better project outcomes not just for those involved Tribes, but the larger society.

A specific comment regarding reporting and grey literature. The traditional model of creating a standalone report with background (often boilerplate), setting, field methods (standardized), field results (including geospatial mapping and artifact catalog), interpretation, and results was born of the 20th century. Maybe it’s time to leave it there.

A better way to envision a report is as a virtual document that is assembled for the reader, but the bits and bytes reside in different places. Leave aside the background section and results and interpretation for the moment. The setting could be pulled from a multi-layered environmental GIS, requiring only the delimiting of the project area as a polygon. If the GIS is a cultural GIS, the known site information would be embedded automatically. Field methods are generally standardized and usually reference guidelines. All that would need to be added are any exceptions to the methodology. Field results belong in the cultural resources GIS, albeit at a much finer grain. Every testing unit could be plotted in space, and linked to its stratigraphy and contents. The artifact catalog should reside in the state’s larger artifact collections catalog. Photos, drawings, and the like could also be tied to units within the cultural resources GIS and reside there as well. What the reader would see is pulled from these various databases and linked through the common project identifier. Instead of being written as a standalone set of data, each portion would be written once into their respective databases. When needed, they would come together into this “report.” A version of this could be found in the Digging I-95 effort.

The background section would also be pulled from another source. That would be the synthesis of the history of the region, or state. Think of it like a Wiki-page that could include chronology, geography, themes, with regional syntheses (from Western and Indigenous perspectives), and research topics. A model for this does exist in England, aka the East Midland Historic Environment Research Framework.

The point of establishing a Wiki-like environment is that it could be amended and modified one project at a time. And it would replace any of the published state-level synthesis, titled, “The Archaeology of (fill-in-the-blank).” For the background section of a project “report,” the geographic location of the project would direct which section of the synthesis would be pulled.

The conclusions of the project, presumably stating what the important information was gained from the work, would be entered into the synthesis Wiki-site as new information, then pulled out again for the purposes of the “report.” The important (Criterion D) information gathered from a project would always be within a context of what is known and clearly differentiated from it. As much of the information contained within the Wiki-site would be available to the general public as could be done, recognizing that some of the information would remain sensitive.

There are several advantages to this approach. First, it would greatly standardize the collection of archaeological information. It would also ensure the GIS and artifact catalog information would be entered into their respective databases up front, instead of chasing these data sets down after the fact, and either re-entering them, or figuring out how to translate field formats. It would also lay bare what was learned from the project and presumably advance the state of knowledge one project at a time. And it would give the public a clearer view of that state of knowledge.

Glad to see this available for all to read. Thank you!

LikeLike